Textile Sculptures of the Visceral Corporeality

In creating faux fabric taxidermy, it takes unbridled imagination and meticulous technique Mesmerizing Flesh The Visceral Corporeality of Tamara Kostianovsky’s Textile Sculptures

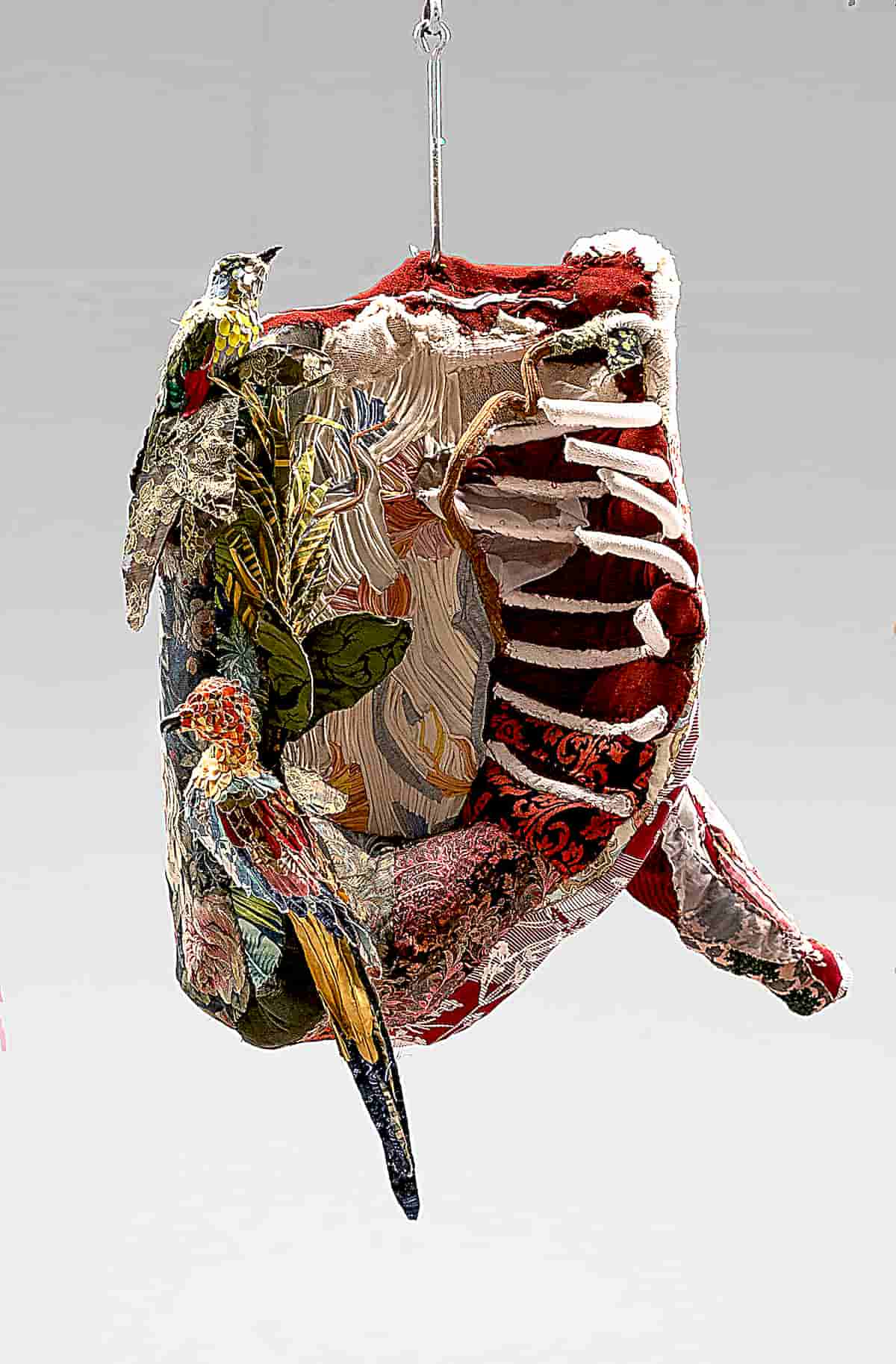

For artists exploring themes of violence towards humans and animals, there is a fine line between thoughtfully engaging and needlessly shocking the viewer; being sensationally explicit can turn people away while being tacit or innocuous may fail to make an impact. New York based artist Tamara Kostianovsky has been successfully walking this line for two decades with her textile sculptures which often take the form of animal carcasses poignantly hanging from metal hooks as in a slaughterhouse. From the mutilated rib cages and leg bones of cattle and pigs to the lifeless bodies of dangling pheasants, geese and other game birds, the gruesome realism of Kostianovsky’s work is balanced by the soft textures and vibrant colours of the materials she uses, namely discarded clothing which she predominantly sources from her own closet. In creating faux fabric taxidermy, it takes unbridled imagination and meticulous technique to be able to transform worn clothes, towels and linens into naturalistic flesh tones, gory ligaments, richly textured animal fat, and exotic bird feathers.

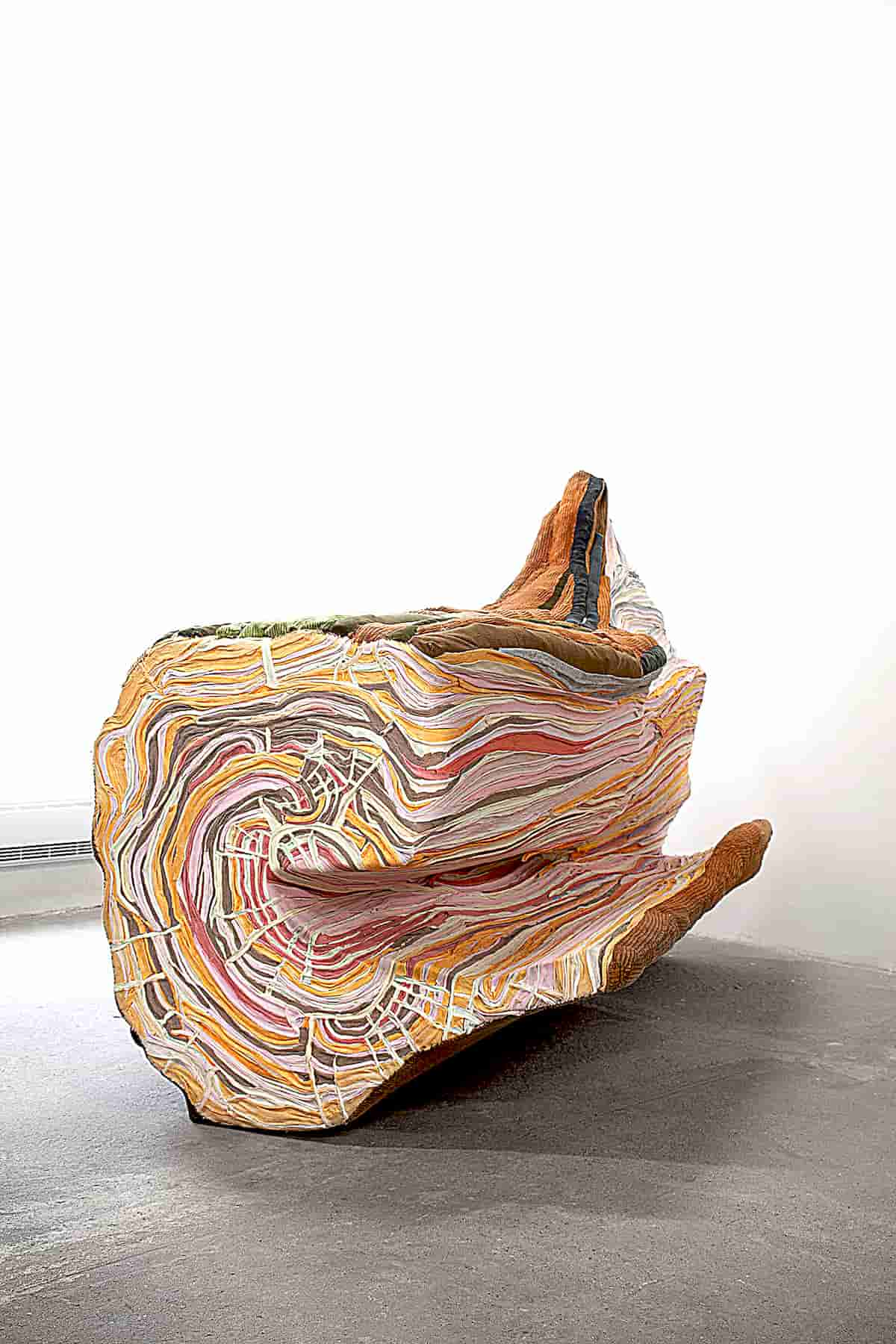

Kostianovsky’s work speaks of our all-too-comfortable intimacy with violence toward animals but her work also touches upon larger sociological, geopolitical and ecological issues. The use of discarded fabric for example speaks of our consumer culture and specifically fast fashion industry’s negative effects on the planet; “Nature made flesh”, a series of flesh-like tree stumps and abandoned logs, are a symbol of environmental devastation; while “Fowl Decorations”, a series of three-dimensional tapestries, subvert the exoticized iconography of colonial-era French wallpaper designs. At the same time, the incorporation of women’s wardrobes into animal remains is a denouncement of the influence of authoritarianism on the female body, an issue she became aware of while growing up in Argentina during the military dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s.

On the occasion of Kostianovsky’s latest exhibition, “Mesmerizing Flesh” at Ogden Contemporary] Arts (on view until April 16, 2023), Yatzer caught up with the artist to talk about her art practice, growing up in Argentina, and her latest series, “Tropical Abattoir”, in which she has infused the animal carcasses with a cornucopia of tropical flowers, birds and vines.

Did you always want to be an artist? What drew you to textile art?

I had an early vocation for the arts. My father was very artistic and encouraging of my interest in the visual arts. I took art lessons as a child, going on to attend the National School of Fine Arts in Buenos Aires after high school. At the time I was interested in painting; it wasn’t until I came to the United States in the year 2000 that I was drawn towards textiles.

In the first few months of living here, I shrunk all my clothes in the dryer— we air-dry our clothes in Argentina and I left my knits in there for way too long. I had bags of clothes that didn’t fit but that I didn’t want to get rid of. To me, these articles of clothing had memories, they were a type of second skin. This anecdote coincided with the big default of the Argentinean economy in 2001 which placed me in a tricky situation. As an international student I had very little monetary resources. I had no money to purchase paints, so looking at my own clothing as art material was a natural consequence of these circumstances. At the time, I was also getting to know the work of Feminist artists from the 70s and 80s who had put their body in their works through their performances. So clothing became a type of surrogate material for my body.

As an adolescent you worked at a surgeon’s office. How did this come about and why did it have such an impactful and lasting influence on you as an artist?

My father was a plastic surgeon. In my adolescence, I would come by his office when he was performing simple procedures (nose jobs, face-lifts, etc.) to let patients in, make coffee and the like. It was there that I gained access to a world underneath the skin where veins exploded into waterfalls, cut ligaments set free the muscles they once contained, and chunks of fat poured over tissues of various colours and textures.

At the time, I was a student at the School of Fine Arts, so the transition from the operating table to painting was seamless. The glossiness and saturation of blood and the stubbornness and intensity of fat tissue were imprinted in my head, and still haunt me today. My approach to painting was very much influenced by what I saw at the office during those formative years.

You were raised in Argentina where meat production has historically played a major role in the country’s economy and culture, while the United States, where you are currently based, has one of the highest per capita meat consumption in the world. Why did you feel compelled to explore this subject? Is there a personal angle?

Meat is ubiquitous in Argentina. In the 70s and 80s, meat trucks constantly delivered cow carcasses to markets all over the country, turning these half-bodies into a silent protagonist of city life. At that time, the Military Junta was ruling the country and a feeling of hidden violence linked to silence and death was breathable in the air.

It was much later, in my studio in the United States that sculptures of carcasses suddenly revealed themselves to me, like an apparition. Made out of my own clothes as a kind of self-portrait, they spoke about gendered violence and the ravenous needs of the body. Over time I became sensitive to the horror and immorality of factory farming and its effect on climate change but at first my focus was more on violence towards humans. More recently, I started considering the body as a receptor of immense beauty, a site for regeneration and rebirth, with carcasses showing protrusions and outgrowths of exotic birds and plants.

Talk us through your crafting process. Do you use real carcasses and remains as inspiration? Do you design every detail beforehand or do you make decisions on the spot?

I have a big binder with images of carcasses that I continually draw from. I usually have an idea of what I want to make but my plans tend to change quite a bit in the process of making each sculpture.

How laborious and time-consuming is the creation of one of the textile carcasses?

It takes me about two months to create each work. There are weeks when I just observe the sculpture while I work on something else, until I figure out a solution for a formal problem or until I realize that the work is done and needs nothing else. But it’s mostly the former. My work is based on a time-consuming process of refining that involves going back to the work several times to clean it up, to accentuate a diagonal, or smooth out a sharp contrast.

Apart from your own closet where else do you source the discarded clothing you use in your work?

My own closet and my son’s closet provide most of the “supplies”. I also shop for remnants of upholstery fabrics. Sometimes I receive donations from close friends. It’s important to me to have a connection to the materials I manipulate in the studio.

The visceral power of your work is based on the realism of the textile carcasses as well as how they are displayed. Do you always create individual pieces as part of a broader installation?

I enjoy making the big installations when the opportunity arises, but I always make sure that each sculpture can stand on its own.

Your work is rich in art historical allusions. What is the significance of such references?

I taught Art History for a living for many years. I’m particularly drawn to images of flesh that populate the history of art, Rembrandt, the Dutch Still Lives of the 17th century, Goya, and Brazilian artists Artur Barrio and Adriana Varejao come to mind amongst many others. In my mind, the connection to these references links my work to a tradition of art makers. I’m in the company of some great artists when I work alone.

You have a talent for striking a poignant balance between the grotesque and the lyrical. How difficult is it to tread this fine line? Is this something you consciously strive for or does it come naturally through your creative process?

I try to work on this balance consciously.

In your latest series Tropical Abattoir, exotic flora and fauna provide a counterpoint to the raw, fleshy corporeality of the hanging carcasses in what appears to be a confluence of all your previous series. How did the series come about and how does it relate to your previous work? Is there a message of hope therein?

No artist today can ignore or escape the severity and urgency of the climate crisis. A few years ago, I started developing a series of works which imagine the metamorphosis of carcasses into landscapes of lush vegetation, populated by exotic birds. Using discarded clothing as the main material, these new sculptures embody the transition from a “slaughter culture” to a model of fertility, regeneration and sustainability. Underscoring ecological embodiment and interdependence, these works challenge the modern myth of transcending one’s material conditions, making a shared material nature visible among all living beings.

What are you working on right now?

I am getting ready for my first solo exhibition in Paris (“Bestiare” at Gallery RX, opening on September 2) and working on a series of wall-mounted maps, where cartography and meat intersect to reveal bloody histories of colonization and plunder. I’m also preparing for a solo show at the Baker Museum in Naples, Florida (“Botanical Revolution”, opening September 5) where I will present new works incorporating the native flora and fauna of the Everglades.

Om onvervangbaar te zijn, moet je altijd anders zijn.

Er zijn fascinerende beelden hier, en de fascinerende dag van samen! xo

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Per essere insostituibili bisogna sempre essere diverso.

Ci sono immagini affascinanti qui, e l’affascinante giornata di insieme! xo KanikaChic