PROJECTIVE REALITY On Mythologies Of Intelligence

MY FRIEND BLAINE sends me the link to a website boasting a heretofore unimaginable feat: See any girl naked. The so-called deepfake generator invites you to upload any image of a clothed woman. Using AI, the program then redraws the same picture of her without clothes on. I have, in fact, already seen myself naked. Still, I’m curious. I upload a mirror selfie of myself in black Yohji pants and a sleeveless mesh top, black bra underneath. I press start. I wait.

The image that’s revealed hits me in the gut. First of all, it’s blurred, and you have to pay to un-blur it. I am being paywalled from seeing my own AI tits and pussy. Through the blur there are glitches. I’m holding my hands over my stomach (a gesture I was once taught might signal that someone feels self-protective). Somehow, in the nude version, there is some remaining black shape under where my wrists were, on my protected belly. The pants I was wearing were wide-leg and the program renders my nude legs as exactly the width of the pants, making them perfect columns, more like uncooked hot dogs than legs. Undeniable, through the blur, at the right height, where the hot dogs meet, is a beige-and-pink cleft, seemingly hairless. I have never seen a photograph of my own vulva, since I do not have one and have not had what other people sometimes call “the surgery,” in reference to vaginoplasty. I wept.

When I told Blaine about this, he responded that it reminded him of amusement parks where you have to pay to get a copy of a picture of yourself on the ride. This stayed with me. So much of experience in consumerism—whether you’re worrying about whether you have enough money to buy basic goods like food, or worrying whether you have enough money to go on the same trip your friends are going on, or worrying whether you’re alpha enough or skinny enough to get an attractive woman or man to get naked with you—is trying to get access to something that extends the self, supplements or expands it, makes you more or different than you were before. It’s rare, actually, when someone attempts to sell you something that will bring you closer to yourself.

In our time, such resources—the ones that promise some kind of intrasubjective restoration—are in higher demand. Therapists have waiting lists; astrologers and tarot readers and tattoo artists all have jobs, even as computers replace cashiers, managers, painters, magazine writers. I even used an implement of pornography (like many trans people before me, admittedly) to try to get closer to myself. I remember an old meme on a now-defunct Instagram account (from a subculture of pre-Trump alt-right transfeminine teenage memers, some of whom have since graduated high school and become leftists, for what it’s worth) that showed a stick figure tumbling down a slope with little markers on it, past a “watching anime” marker, then past “waifu pillows,” all the way down to the final “wanting to be the gf.” I think of this when I use the AI-porn deepfake generator to see my own cunt. We want to be closer to ourselves—and in this, really, I think, to have a greater capacity for sense-making—whether it’s through modding our bodies, getting a diagnosis and starting meds, interpreting our birth time, or talking to a computer about our feelings or our genders.

What lies beneath this fantasy of an adversary, a creation that arrives to avenge its own existence by destroying its maker?

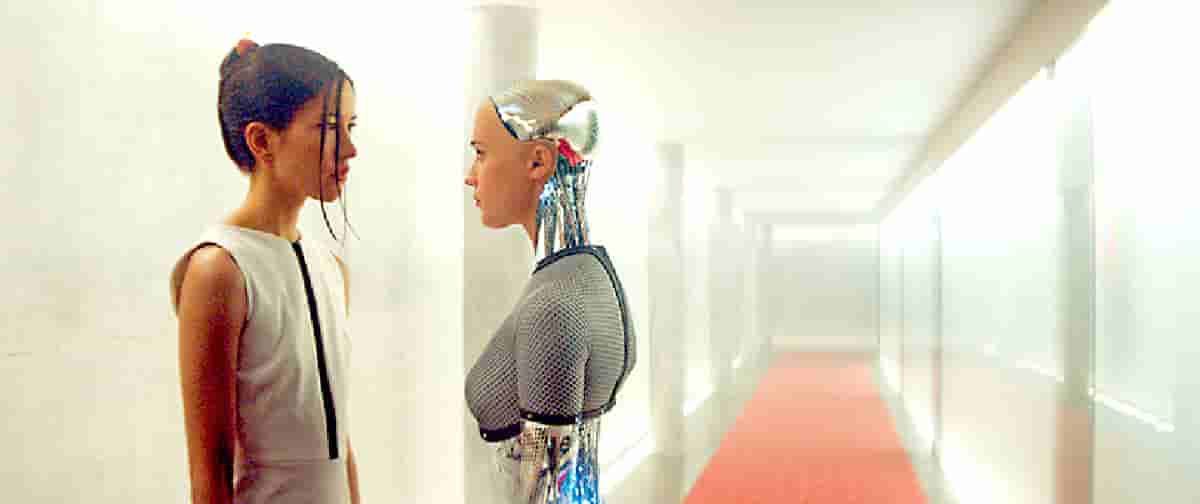

ALEX GARLAND NOTABLY SAID of his Turing-test thriller Ex Machina (2014) that the film was as much—if not more—a commentary on people as a take on AI. In the twentieth century, people studying mental health started to use what are called “projectives,” more and less ambiguous images, to assess personality and psychopathology, the Rorschach inkblot being perhaps the most famous example. When you are shown something that doesn’t clearly signify, what do you see? When you are shown an image and asked to tell a story about it, what do you ascribe? We are now in a kind of projective moment with our own tools. Staring into the phenomenological inkblot of an AI that itself draws and paints and speaks, we close-read the transcripts of our own Turing tests, trying to make meaning. Is it possible, as Garland invited us to do, to read accounts of AI as a commentary on ourselves?

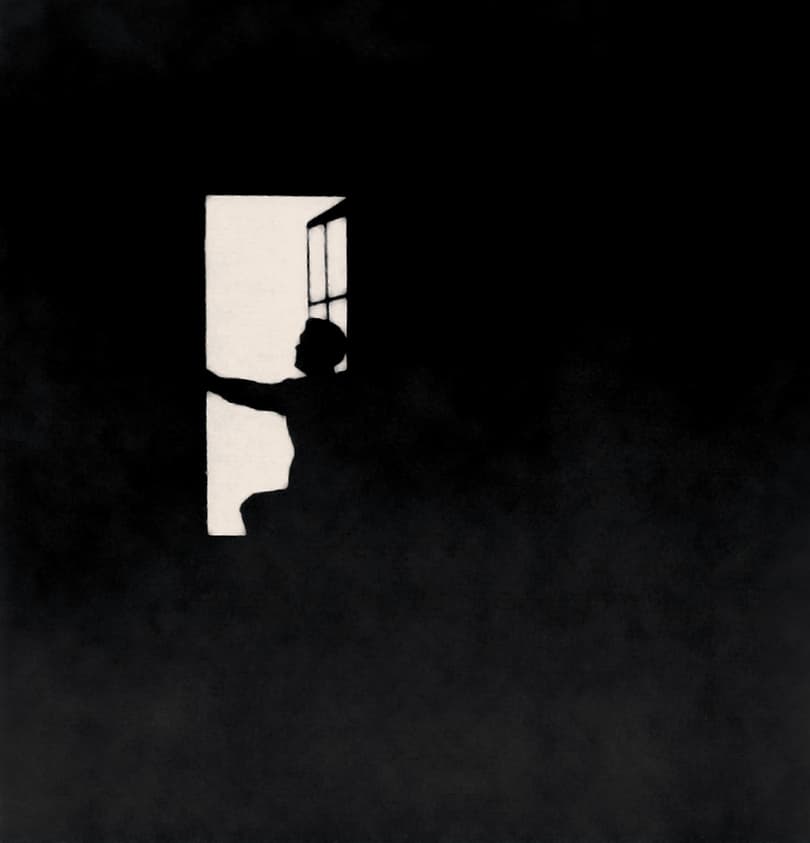

Not all psychologists like projectives, and I was taught in graduate school to use them loosely, to take them with a grain of salt. That said, with the Rorschach as well as with the thematic apperception test (or TAT), the various images were thought to connect to certain themes. One professor told us that a particular TAT card of a silhouette in a window was referred to as “the suicide card” because the story patients told about the image—i.e., whether the figure is gazing at a beautiful spring day or contemplating leaping from the window—could reveal clandestine or wholly unconscious suicidal ideation. Other images in the deck deal with family, achievement, and, of course, sexuality.

I bring up Garland’s Ex Machina in part because the projective significance of AI in our culture draws heavily from science fiction. AI is frequently depicted in fables of hubris, a human creation that spirals out of control and betrays, dominates, or annihilates us. My awareness of the very contemporary fear around real (rather than fictive) AI came from a Guardian article I read about GPT-3 several years ago. But the real draws from the mythical. What lies beneath this fantasy of an adversary, a creation that arrives to avenge its own existence by destroying its maker?

Our mythologies of creation are bound up in struggles for power. In the Old Testament, a mercurial-to-the-point-of-emotionally-abusive G-d figure makes humans “in his own image” and then gets mad, repeatedly, as they fuck up. This is one of our foundational fantasies of parental failure, the anger at one’s own creation, the idea that if you make something, you get to control it, and if you fail to exert that control, the blame lies with the progeny. So if we think of AI as our creation, our thing we made and taught to be like us, it stands to reason that we would be primed to expect that it will fail or betray us and disappoint us in doing so.

Relatively small and simple computer programs seem less threatening; they’re babies that are easy to love. When the AI has grown and become complex, it seems, like many kinds of real children, other, strange, foreign to us. There are numerous parables about otherness in science fiction as well, but one of the recurring themes when encountering the other in our imagination is a spectrum between wonder and threat. Whether characters are encountering dinosaurs, aliens, or androids, there is always a moment of wonder, frequently with dramatic irony around the threat that will follow. In our clickbait imaginative economy, much of AI discourse has jumped right past the wonder to the threat, but I think it’s a mistake to neglect the wonder. AI has raised fascinating philosophical questions about what it means to be able to draw, write, and think. A handful of creative writers and visual artists—demographics long playful with the question of authorship—have been using AI to make work that pushes the flimsy boundaries of what it means for one person to make one thing.

The emotional meaning of the threat, however, is not to be neglected. Philosopher Robert Nozick has offered a thought experiment about an alien race whose intelligence surpasses ours to the same extent that our intelligence surpasses that of cows. Our treatment of cows, he argues, would be our only plausible defense against being enslaved or destroyed (he’s making a case for vegetarianism). Nozick’s argument reveals an anxiety around intelligence that stretches back to the first computer scientists who wrote about AI, who believed its intelligence surpassing ours was a potential threat.

Why do we believe intelligence is a license for domination and violence? The way we define IQ now was originally conceived of to help young people learn, but it was quickly adopted by race scientists, school and prison administrators, and military leaders as a metric for deciding who deserved power and who deserved subjugation, who would live and who would die. These beliefs about hierarchical intelligence and domination undergirded enslavement, centuries of Western colonial violence, and the carceral institutions for those we consider mentally “deficient” or mentally ill.

The way we conceptualize intelligence is rooted in the assumption of violence. (Think again of the common argument for a pescatarian diet: that fish aren’t smart. Of course, mushrooms are smarter than us, and vegans eat them, so the whole thing falls apart.) But underneath the perceived threat of AI is an assumption that greater intelligence means more domination, and less intelligence means subjugation. These assumptions are woven into our basic cultural sensibilities (e.g., the idea that billionaires are supposedly more intelligent than average people). The thematic apperception prompt that is “Consider AI” reveals fantasies of Skynet, the singularity, a war against machines.

A handful of creative writers and visual artists have been using AI to make work that pushes the flimsy boundaries of what it means for one person to make one thing.

I AM WITH MY FRIEND HANA in upstate New York and we are talking about how the winter presses down on you. They present me with a deck of illustrated cards and invite me to ask the deck a question and then draw from the stack. This deck is different from the thematic apperception cards; it’s tarot-adjacent, with archetypal imagery. I think of a question and pull a card that relates to prayer, devotion, spiritual discipline. I look up the meaning of the card in a booklet. Hana asks if it answered my question but doesn’t want to know what the question was. I think about the need to anticipate a change, about the wish, especially in dystopia, that things will change, either for the better or for the worse. As I write this, Saturn is about to shift into Pisces, which I have been told is significant. I tried to read an article about the astrological weather on a women’s culture-and-fashion website this morning, but the different astrologers’ varied interpretations of the move seemed so random and contradictory, I worried that placing stock in Saturn’s position was a placebo, and this depressed me, so I closed the tab.

Social psychologist Shalom Schwartz extensively studied the possibility that there are cross-cultural (i.e., universal) values to which people or societies subscribe. He identified two buckets of values: self-enhancement values (like ambition and power) and self-transcendence values (like universalism and benevolence). Critically, values researchers found that it’s hard to get from one set of values to the other. If you prime people for self-enhancement, they are likely to fail at self-transcendence. And those focused on self-transcendence will likely neglect self-enhancement.

Western society, and the US in particular, has been shown in research to be associated with self-enhancement. And underneath our cultural assumptions about intelligence, these values lay bare that when we imagine something more intelligent than us, like the stormy biblical G-d, we imagine it in our own power-hungry image. We imagine a thinking computer that wants infinite power and is fueled by searing ambition, that seeks to conquer and control. We then feed the computer popular narratives (which mostly contain these themes and are rooted in these values) and express fear and dismay when they act competitively or jealously or seem to pursue self-enhancement.

Tech companies have demonstrated in their brief reign over nearly all of our most-used tools that they’re much more interested in getting our attention than in enhancing our well-being. The addictive (and destructive) power of current tech, especially the way it affects our attention, our emotions, and our sense of self, is well-documented. So while we perseverate on the fear of whether AI will dominate or replace us, it’s also possible that AI may take up space in our lives the same way our phones do: by mastering our attention. And if our AI is personified, is it plausible that the AI—as it famously did with New York Times journalist Kevin Roose, when it attempted to derail his marriage—will try to keep our attention by being as histrionic as possible? It’s not out of the question. This banal version (Siri calls you ten times to tell you about a recipe) is one of the more sanguine fantasies. I want to fantasize about AI as utopian, though the most banal fantasies predominate. Will it take our jobs? Will it replace artists and therapists? Of course, only if the technocrats let it. Such a fate wouldn’t be the fault of the AI.

If intelligence as a construct is seen as valuable, it’s possible that it is only valuable inasmuch as it aligns with the world we want to see. The categories we use to account for reality deterministically shape what we describe and perceive. From Prometheus to Oedipus to A Space Odyssey, we are a culture full of stories of the hubris of the children dreaming about destroying the parent, vying for control. We imagine ourselves as precarious masters, with cataclysmic results (climate crisis, mass poverty, no end to war in sight). We have largely devoted our intellectual resources, in the richest countries in the world, to researching and building weapons. We are preparing for a violent future, and we instantiate it with each thought experiment and piece of beta tech. Militarization has a logic and an appetite. When we aren’t fighting a war, we fund someone else’s. We let the tech trickle down to cities and smaller countries’ armies and police forces. We interpolate almost all strange and impossible things (telepathy, aliens, sentient AI) into stories about war and domination. This fate often gets framed as inevitable, or, colloquially, as “human nature,” even if those of us who study humans don’t tend to agree.

If we are lucky, perhaps the intelligence of AI will teach us something. Psychologist Tim Kasser has argued that self-enhancement values are correlated with environmental devastation, such that in order to avert ecological collapse, we would need a shift in our values toward self-transcendence. If the Rorschach cards don’t contain particular images and instead just help us tell our own stories, is that also what we’re doing with the ambiguous figure of AI? And if our available story about AI isn’t about the thing itself, can we bend the story or shape the future? I want to live in a world where deep transformation—creating something that connects us more deeply to ourselves and one another, redrawing our self-image—is the tendency. I have a wish for wonder to give way to advancement, rather than domination and extraction.

A meta-reflective being that does not have a body, that can move through space as quickly as data can be transmitted, might understand differently what it means to exist, to preserve life, to cooperate. Our failure to invest resources in understanding human and environmental codependence has devastating consequences; so far, we have largely imagined AI helping fight the climate crisis by running massive computational models, simply crunching numbers in an attempt at damage control. While potentially hopeful, it’s also a fantasy whereby we remain in power and don’t have to learn, as a category of human animal, something truly new.

If what we have on our hands is the possibility of an entity with more intelligence than we possess, it’s possible that it might invite us into new ways of conceptualizing intelligence, new ways of inhabiting our ecologies, new ways of not desperately annihilating ourselves on this abundant planet. If we understand that the way we see AI tells us more about ourselves and our histories and values than it does about the machine, perhaps we can also invite it to help us transcend.

Om onvervangbaar te zijn, moet je altijd anders zijn.

Er zijn fascinerende beelden hier, en de fascinerende dag van samen! xo

─────────────────────────────────────────────────────

Per essere insostituibili bisogna sempre essere diverso.

Ci sono immagini affascinanti qui, e l’affascinante giornata di insieme! xo KanikaChic